Introduction to Genetic Algorithms in C#

May 14, 2013

A long time ago I mentioned in this post that I was planning on writing up some notes I made at university about Genetic Algorithms (from now on, known as GAs) and my version of a very simple example in C#. Years later…here it is! C# isn’t the most popular choice for artificial or natural intelligence programming, that job is largely the domain of Java or other more academic friendly languages. This means there aren’t a great deal of C# examples out there for neural networks, search and genetic algorithms and programming.

Barry Lapthorn wrote a C# example a while ago, which is on Codeproject (I’ve converted it to .NET 4 here), however for the very basics of GAs his article can be a bit unwieldy as the example uses doubles for its genes - using a floating point number for a genome or gene value is fairly common in the science world, however it makes explaining the mechanics of GAs a lot harder to write without going into depth about representations of a gene.

I’m going for the keep it simple stupid approach, sticking to bit strings for each gene. One thing I will point out right at the start (which should be obvious) is I am by no means an expert in the field of Genetic Algorithms or biologically inspired AI. I’m not on the cutting edge of the subject and this post certainly isn’t aimed at presenting that to you.

The basis of the information here is from the original 1970s book “Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems” by John Henry Holland, which is how I was taught it at University a few years ago. If there are any errors in my information please correct me the comments.

A brief introduction to genetics

As you’d expect, the world of biologically inspired AI and genetic algorithms relies on simplified concepts taken from biology, and the area of genetics. This includes genomes, genes, cross-over, mutation, generations and fitness selection (coined as survival of the fittest).

A genome is the entire set of genes for a species, which in the case of human beings contains around 25,000+ genes.

Each of these genes in turn contains a sequence of DNA. The DNA is made up of two strands which are gelled together with a combination of 4 different amino acids denoted with the letters A C G T - based off the amino acid they represent, e.g. G is guanine. Every cell in our body contains our DNA in the nucleus, in compacted form known as chromosomes (there are 46 in humans). The chromosomes come in different shapes, men have X and Y shaped chromosomes while women have two X. GAs don’t concern themselves with the DNA or chromosome level of detail, instead stopping at genomes and the collection of genes inside them.

When two species reproduce, the genes of each genome are split so the offspring gets half the genes from one parent, and half from the other. This is the cross-over stage in a genetic algorithm and accounts for why a son may look like one parent rather than the other - the cross over may have taken almost all the genes responsible for this trait from the mother or father.

During the lifetime of a species, or during reproduction, mutations(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mutation) can occur that will change the structure of the DNA to something new, or in the case of GAs altering the entire gene. The term mutation usually has negative connotations, but it can be beneficial as well as harmful, some mutations increase the fitness of the species.

Fitness is simply the species’ ability to survive in its environment. Predators may adapt to outsmart its prey, and then the prey adapts back to outsmart the predator, a subject in evolution known as co-evolution.

The lifetime of the species is a single generation. Each time you get reproduction (and with that crossover and mutation), a new generation is born.

Genomes and genes

With all that information in mind, you’ll be glad to find out genetic algorithms simplify everything a lot by simply having a genome, and within it a set of genes. And for this post a gene is simply a bit: 1 or 0. So for example you might have a genome, that contains 4 genes:

[ 0 0 1 1]

Obviously a population needs more than 1, so you’d have two genomes:

[ 0 0 1 1] [ 1 1 1 1]

Where 1 1 1 1 represents the second organism.

The starting point when creating your GA is to consider how you will model your problem as a genome and set of genes. You need to figure out exactly how many genes you want for your genome. The representation I’m using for this post is based on each gene being a single bit - 1 or 0, and a genome containing 6 genes.

The example I’m using in this post is a GA to find the optimum combination of genes for rolling of two die, which was the example I was taught. We want to establish which genome is fittest for producing the highest number from the roll - we obviously know this will be 12 - but the point is to demonstrate the machinery involved in the GA.

As 6 in binary is 110, and 111 is 7 the example will be two dice with numbers 1-7, which simplifies the bit representation. A dice with 7 possible values can be represented like so in binary:

001

That string gives you every possibility of the dice: 001,010,011,100,110,111

or in decimal:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

We are representing two dice so our bit string will be two lots of a 3 bit number, 6 bits in total, for example:

001 110

This would be 1 for the first dice, 6 for the second.

Object representation

The OO way of I’ve chosen to represent a Genome and the world they live in is fairly straightforward:

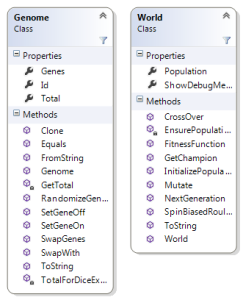

Genome contains an array of genes, which is just a bool[]. It contains a set of helper methods for cloning, initializing itself with random values, setting genes values on and off and getting the total based on the the array of bits.

The World class does the bulk of the operations of the GA, and contains a Population property which is a list of Genome objects. The size of this list is the population size, which should be an even number. The World class is responsible for all the topics I’ll go through next: mutation, cross over, fitness function, the biased roulette wheel and creating new generations.

Fitness functions

The first step in creating a GA will usually be working out how to figure out if you genome has reached the optimum of what it’s supposed to do, for this example this will decide which combination of dice gives the highest number. The function that works this out is called a Fitness Function in GA parlance. Our function is passed one of our genomes (6 genes in our case), and figures out the total:

public virtual int FitnessFunction(Genome genome)

{

return genome.Total;

}

The total is figured out using the bool array:

The fitness of the gene is based on the number it represents, and one of the hardest parts to GAs is thinking how to encode the problem you have as a series of bits, and then writing your fitness function to decide how fit the genome is.

The mating pool and initial selection

Now that we know what the genes represent, and how to decide which genomes/genes are the fittest for our environment (in our environment the number ‘14’ is king), the next step is to create a mating pool. This is the initial set of genomes, aka our population/world. To make this simple to figure out, we’ll stick 4 genomes in our pool to start with. With these four genomes, we then randomize the genes (or bits) for each of the four genomes. So in C# this is fairly straightforward:

Output: 001 011 (1,3) 001 100 (1,4) 001 110 (1,6) 101 100 (5,4)

The bracketed numbers on the right indicate the decimal equivalent of the binary number, so 001 is 1 in decimal, and 001 is 3: (1,3). Each genome is now ready to “mate” with another genome. To do this we need to select, or dip into the gene pool.

The biased roulette wheel

Ordinarily we want to select the best genes from our gene pool to mate, giving us the “survival of the fittest” (as Darwin is often misquoted as saying). This sounds great in practice - if the random bits we generated in the previous step are all ideal then we’ve solved our problem straight away. In reality this is not what we want to do with a GA. The power of GAs come from mutations and crossovers between genomes rather than simply selecting the best first. In the dice example we’re using it’s not that easy to see why we’d want to mutate and crossover, but keep in mind that this example is very simplistic, and for more complex problems mutations are required in order to get away from something known as the local maximum, where we think we’ve got the ideal solution but in fact have only reached a mini-peak in the mountain we’re climbing up.

So given the previous step of selecting four genomes, let’s assume our population is primed with the following random genomes:

110 010 (7 and 2 = 9) 000 101 (0 and 5 = 5) 100 001 (6 and 1 = 7) 010 011 (2 and 3 = 5) Total of all genes = 26

We don’t want to just pick the top genomes to mate based on the fitness function as we want some randomness. However at the same time, we want to retain the traits of the fittest genomes otherwise the whole procedure would be fairly pointless.

To ensure we keep the best genomes, a selection technique is used that gives bias to the fittest ones whilst also letting weaker ones through. This technique is known as the biased roulette wheel and is a form of stochastic sampling.

The way this works is in several steps:

Work out the total fitness values of the genomes: 9 + 5 + 7 + 5 = 26

Work out the weighted value of each genome: the (genome fitness value / fitness total) x 100

For example: Genome #1 = 9 / 26 = 0.346

Turn into a percentage = 0.35 * 100 = 35%

Each of these values represents the percentage chance that the genome has of being picked

Roll a number between 1-100. If that number lies within the genome’s percentage number, it is picked. For example rolling 35 would pick the genome, rolling 40 wouldn’t

Here’s how the roulette wheel is implemented in the solution download:

The random parameter allows the tests to pass in their own stubbed implementation of the Random class, enabling us to test the method with a fixed number. The method returns the first Genome it finds whose percentage value is inside the range of the random number.

The test for the SpinBiasedRouletteWheel method in the solution simply fills the population with 4 genomes, and gives the method a stubbed Random to check it’s picking the correct one.

Crossover

You may be wondering how we mate two virtual genes, but the process isn’t actually “mating” but a combination of two biological inspired functions: crossover and mutation. Cross over involves swapping a set of genes between the two genomes (mimicking chromosomes) and mutation is simply swapping genes inside the genome.

One of the most important parts of GAs is the crossover and mutations, without this we get no improvements or variations in our populations, defeating the point of aping evolution in the algorithm. To perform a cross over, we simply take the two genomes we have picked for mating, and swap their genes at a certain point.

This is best illustrated with an example. Let’s say our roll of the roulette wheel has picked the first two genomes:

110 010 000 101

We then pick a point (using a random number between 1 and the number of genes in the genome) and swap the genes before (or after) this point. Let’s say the position to swap at is 3 and we swap everything up to and including gene 3:

110 010 000 101

becomes

000 010 110 101

We’ve produced two new genomes, children of the previous two genomes. These two new genomes are placed back into a new mating pool, which is the basis for our next generation. In order to keep the population constant, we do this one more time so that our next generation has 4 new genomes in it.

One thing to note is crossover isn’t performed every single time, but is based on a random chance of it occurring. This is your crossover percentage chance, which your GA is setup to have as a variable or constant. Here’s the C# example

Mutation

Finally we incorporate mutation into our GA. Like crossover, this is not performed every single time but rather has a percentage chance of occurring based on a constant or variable.

The mutation occurs before the two genomes are crossed over, by swapping a gene in one genome with another in the same genome, the position of this gene is based on a random number. So once we have picked two genomes from the roulette wheel for mating, each one is evaluated to see if it should mutate. If it should, we pick a number between 1 and the genome length for each genome, and swap those two genes around.

Mutation rate should remain low in a GA to avoid any improvements we’ve made from previous generations being undone.

And finally

With all of this in place, this is how I made the unit test that tests everything together (Test):

- Create the world

- Spin the biased roulette wheel

- Perform mutation

- Perform crossover

- Do any of the genomes meet the fitness function?

- No…repeat from step 2

- Yes…we’ve solved the fitness function puzzle.

Here’s some console output from the test above test, where the mutation rate was 5%, crossover rate is 30%. Each block is one generation, and it took 883 generations to reach the fitness function criteria:

111 110 (7,6) 010 010 (2,2) 010 010 (2,2) 111 110 (7,6) 011 110 (3,6) 011 110 (3,6) 110 010 (6,2) 011 110 (3,6) 011 110 (3,6) 011 110 (3,6) 011 110 (3,6) 011 110 (3,6) ... 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 111 (6,7) 110 101 (6,5) 111 111 (7,7) 111 101 (7,5) 110 101 (6,5) A new leader is born! generation 883 - 111 111 (7,7)

If you play around with the crossover and mutation rates, you’ll see that the number of generations increases and decreases, particularly when the mutation rate is over 50%, or the crossover rate is low. A zero crossover rate will unstick the GA, and is unable to xyz.

As I mentioned at the start, this post really is scratching the surface of genetic algorithms, and after this it gets a lot more involved (or complicated if you prefer), with theories on the templates of the genomes coming into play, known as schema theory (more info here).

I'm Chris Small, a software engineer working in London. This is my tech blog. Find out more about me via Github, Stackoverflow, Resume