C# Bit manipulation by example (part 1)

December 22, 2010

This is the first part of two blog posts trying demystify bit manipulation in C/C#.

Below are several topics that I found useful background knowledge for bit manipulation (whether it’s in C#, C or Java - any C based language but this page is written with C# in mind). The most important topic is obviously knowing how to count in binary, but also knowledge about 1s and 2s complement form bit shifting.

Counting in other Bases

I wasn’t sure whether to spend my time writing up my notes on counting and arithmetic in different bases - a lot of it is derived from internet resources and a university course. I came to the conclusion there was no point duplicating content that’s already out there elsewhere so this section has a lot of details skipped, with just the important parts that I feel are/I needed. Probably the biggest concept to grasp about different bases is the idea of each column going from right to left, containing the base times the previous number.

In base 10:

10: 1 x ten

37: 3 x ten, 7 x one

345: 3 x 100, 4 x 10, 5 x one

Looks like something you were taught at aged 6, if you remember back then. You take the knowledge for granted, however Base 2 or binary counting goes like this:

1: 1

10: 1×2,0x1

10101: 1×16, 0x8, 1×4, 0x2, 1×1

As we go from right to left, each column represents 2 times (in base 10 this is ten times) the previous. Drawing a table with each column representing the number of the units is the simplest way to represent it.

128s 64s 32s 16s 8s 4s 2s 1s 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

The above table is analagous to a display of bits (grouped in 4s):

1111 1111 or 255.

As you can see the binary notation maps to bits easily. I hope it’s not a revelation to tell you there’s 8 bits in a byte, and that your desktop PC will be described as 32 bit or 64 bit, meaning each memory address stores in blocks of 32 bits/4 bytes or up. Hexadecimal, being base 16, is ideal for displaying the value of 4 byte addresses. Octal use to be the preferred base for this (base 8) prior to x86 as the wikipedia article on Octal will tell you.

You’ll find lots of articles on hexadecimal out on the web, so I won’t repeat or attempt to write my own explanation for it - the links at the bottom are some good places for this. One thing I’d like to show is a similar table to the one above:

4096s 256s 16s 1s E 4 F E

To me, that simplified hex a lot. You have E (A=10,E=14) or 14 lots of 1s. F or 15 lots of 15s and so on. This takes a lot of the complication of counting in hex out of it. Most of the time you won’t be counting in hex unless you get a real kick out of it, but it’s still useful and satisfying to know what is going on.

That’s about all I have to offer in this small disjointed section on binary and bases.

Sign magnitude and binary display formats

For your 32 bit machines, you would expect a display of a 4 byte number (an Int32) to be display with 32 bits:

1000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

But for the basics of binary and bit manipulation, it’s easier to start off with just 8 bits:

1000 0000 (which is 128)

This is known as true binary form. It has no bit to denote whether the number is positive or negative (explained later). This format is fine for starting off when learning about bit manipulation, and getting your head around the concepts, however numbers aren’t stored in this format.

One other noteworthy way of displaying binary is Binary Coded Form or BCD. This displays each decimal column as 4 bits. For example 127 is:

0001 0010 0111 1 2 7

This is a very simple format to read and write binary in, however it’s not really relevant for bit manipulation with this article. The Wikipedia article gives a decent explanation.

Sign magnitude is concerned with how many bits we are using to represent a number. For example 4 bit sign magnitude is:

1111

As you’ll see in the next section, it’s almost always 32 bit sign magnitude for .NET manipulation, the only way around this is to downcast to a byte, however this get upcast again with using numerical literals.

Numeric literals

In C# much like other languages like Java, all numbers that are declared are implied to be Int32s (or 64 bit). For example take:

byte x = 28;

While you’ve declared a byte of value 28, it’s stored as an Int32. This becomes apparent when you start performing left bit shifting on it beyond the 8 bits of a byte datatype. More on the topic in this stackoverflow question.

Least and most significant bits, Endian formats.

The least significant bit in a series of bits or binary depends on the way you are storing the bits in memory (RAM). This is known as the endianness, this codeproject article has a good summary of the concept.

The endian format dictates which is the least and most significant byte (LSB and MSB). The least and most significant bit swaps arounds for little and big endian. In .NET the BitConverter can write in little and big endian formats, also Jon Skeet has a utility to convert between the two.

The LSB/MSB are relevant for the sign (positive/negative) of integers and for 2s complement.

1/2s complement (how integers are stored) and floating point storage

The concept of 1s complement and 2s complement revolves around how signed integers are stored in binary. The system for storing negative numbers in binary or as bits is very simple and is known as 1s complement. You simply reverse the bits to get the negative of the number you have. For example

0000 0100 = 4

1111 1011 = -4

2s complement takes this one step further, and enables fast calculations on the ALU (the arithmetic logic unit) on the processor. Infact, an ALU can do subtraction, addition, division and multiplication with one fast circuit using the 2s complement system.

In 2s complement, you add one to the least significant bit. That’s all there is to it, but to illustrate here is an example (taken from http://gs.fanshawec.ca/tlc/math270/1*4**Storing*Integers*in*Binary.htm which is no longer available):

- Write +39 in binary: 0010 0111 [39 = 32 + 4 + 2 + 1]

- Take the one’s complement (invert the contents of the byte): 1101 1000

- Add 1 to the LSB

- The answer is the two’s complement of -39: 1101 1001

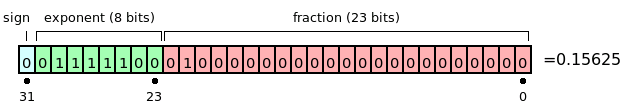

The 2s complement system is relevant for integers. For floating points it gets a lot more complicated - a 32 bit Float (aka Single in c#) is made up of the following:

32 bit (4 byte storage made up of):

- 8 bits (1 byte) for exponent

- 1 bit for the sign (+ or -)

- 23 bits for the fraction (known as mantissa or significand)

Jon Skeet has a lot of information on the subject on this page, plus other links to even more detailed information.

References and Links

Jeremy Falcon’s article on codeproject is probably the best place to get all the information above in more detail.

I'm Chris Small, a software engineer working in London. This is my tech blog. Find out more about me via Github, Stackoverflow, Resume