Roadkill reaches the magical 1000 unit test mark

December 23, 2013

Warning: this post contains large amounts of pro-automated-testing propaganda.

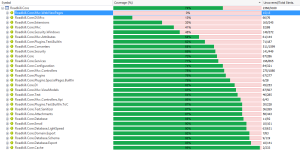

Roadkill is now up to over 1000 tests (around 1150) as it gets near the version 2 release coming in 2014. Around three hundred of these come from the Markdown parser that Jeff Atwood wrote, and the HTML sanitizing toolkit, but the others have all accumulated over the past year including a lot of retro-fitted tests which were written to aid refactors. The test coverage is now around the 75% mark according to Jetbrain’s DotCover tool:

Looking at these bar charts you can see the MVC namespace is only 50% complete, along with a few others. A lot of the parts that are 0% or in the lower percentages are down to parts of the system which you can’t practically test due to the internal workings of the .NET framework (the Active Directory namespace for one), or won’t give you much benefit or assurance from testing.

TDD discussions seem to be a little bit like language discussions on the internet, there are a lot of TDD zealots and also haters. One of the key things that is often lost for both sides of the argument is the practical reason for unit tests and the whole purpose of the tests in the first place. They are there to save you time, “automated tests”: the clue is right there! You are proving that the software you have written is correct in so much as the expected outputs match the inputs and, equally as important, you save time from avoiding having to do this manually.

I’ve found TDD a good tool for designing your software, but not the only way you can write software and in my view is often in-practical for designing parts of the system that require you to cross layers. The new plugin architecture in Roadkill was a good example of this, one particular plugin that syntax highlights on the page has to parse a new token [[[code…]]] but also has to inject the plugin into the DI container, inject Javascript into the view and run the Javascript, and load its scripts in a certain order. The parsing of the token was easy enough to unit test, but on its own didn’t give me great confidence that the plugin actually worked. For this particular plugin it was left to a manual testing, but most of the time this is the job to the far more useful integration, acceptance and regression tests, which give you glimpse of the whole system failing.

One of the nice features of Dotcover is it shows all the branches/paths that you are missing test coverage for. In Roadkill I had no unit tests around a lot of my guards (ArgumentNullExceptions) which I felt compelled to fix, and was able to largely because of the project’s status as a labor of love and not costing me anything to write, except for Monster drinks and green teas. With that said, if I was to commission somebody to write Roadkill for me, I would make one of the project’s requirements to have close to 80-90% coverage of all paths, largely from the benefits I have seen from doing this with Roadkill.

The tests in Roadkill make a great documentation tool and way to communicate my intent to my future self and others who might pickup the code later on. I’m quite optimistic that not many of the tests in Roadkill are a hindrance rather than a help but I suspect quite a few of the 1000+ tests will have some dodgy setup data that could be engineered a bit better or neater assertions.

Roadkill sticks to the testing triangle:

There are a lot of Selenium acceptance tests in the project which is down to my own preference, as I think close to 100% coverage for your UI is essential for headache-free web-based software. The pattern used throughout Roadkill is “Arrange, Act Assert” - arrange contains the setup, act performs the action and assert verifies the outcome. This is used alongside the tests being named using the similar “given, when, then” pattern (which I think originated from BDD). The two aren’t mutually exclusive but the AAA pattern is less expressive for business software, particular if you have formal acceptance criteria you’re testing against. I obviously don’t have this level of formality in Roadkill and can craft the code however I damn want! The Pony, Zebra, Unicorn pattern if needed.

Roadkill has taught me an enormous amount about fast acceptance testing (Roadkill uses IIS Express and ChromeDriver for this) and unit testing around the ASP.NET MVC framework, since I moved the system from a very basic and untestable (but nicer API) Singleton setup back in 2012, to “turtles all the way down” constructor-injection and DI design. I think I’ve probably shifted large portions of useless but interesting trivia from my brain in the process and a couple of vital pin numbers too - I would even be so cocky to say I could probably write an ASP.NET MVC unit testing recipe book now, and it might even get to over 20 pages! Mocking the HttpContext, HttpRequest and HttpResponse are the basics of this, but Roadkill includes attribute verb testing, HtmlHelper testing, route testing and a fair few extension methods for ActionResult testing. A lot of the credit goes to Darin’s answers on Stackoverflow.com.

Sadly the majority of the .NET framework is not as testable as the new-ish MVC framework: SmtpClient, System.DirectoryServices and the DateTime class all require you re-invent the wheel by extracting the methods you need out into interfaces. In the case of the first two the lack of mockability is probably down to performance reasons, however the DateTime class really doesn’t have much of an excuse. Unfortunately there are also new Microsoft frameworks coming for ASP.NET which are still not designed from the “how can I test this” perspective and concentrate more on a easy to discover API, at the expensive of external unit testing. The Bundles (System.Web.Optimization) is one of these, where testing it is impossible as it holds its HttpContext as a static internal variable.

If you’d like to see evidence of Roadkill’s green ticks, the CI output (from a successful build) is here.

I'm Chris Small, a software engineer working in London. This is my tech blog. Find out more about me via Github, Stackoverflow, Resume